![]()

Inflammatory

bowel disease

The term inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) describes clinical conditions with chronic, relapsing and remitting inflammation of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) are the two most common types of IBD.1

![]()

Irritable bowel

syndrome

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a chronic and relapsing functional gastrointestinal disorder (FGID) – FGIDs are considered ‘disorders of gut–brain interaction’. IBS is the most common of the FGIDs, affecting approximately 5–12% of the population in western countries.2-4

![]()

Coeliac disease

Coeliac disease is an immune-mediated chronic inflammatory disease predominantly affecting the gastrointestinal (GI) tract which is caused by the ingestion of gluten-containing grains. It is a common lifelong disorder, with a prevalence of 0.5–1.0% in Caucasian populations.5,6

Inflammatory bowel disease

The term inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) describes clinical conditions with chronic, relapsing and remitting inflammation of the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Crohn’s disease (CD) and ulcerative colitis (UC) are the two most common types of IBD, both of which are heterogeneous diseases at the clinical level.1 They are chronic immune-mediated diseases characterised by a dysregulated immune response in genetically susceptible people.2 UC is limited to the colon while CD can involve any part of the GI tract from the mouth to the anus. Age at diagnosis, location and extent of disease, and disease behaviour are major factors affecting disease course and prognosis.3,4 IBD can be diagnosed at any age, with usual age of onset between 15 and 45 years.5

Risk factors for inflammatory bowel disease

The two most common risk factors associated with inflammatory bowel diseases are genetic predisposition (NOD2 or IL-10 gene mutation; Ashkenazi Jewish heritage) and smoking.1 If two parents have CD, there is a 50% increased risk of their child developing the disease. For Ashkenazi Jews, there is 17% increased risk.

The recent increase in incidence6 and changes in disease risk occurring with migration7,8 suggest environmental factors also play a role in the pathogenesis of IBD. One possible mechanism by which the environment influences disease risk may be via the gut microbiome.2,9-14 This, together with the concordance reported in familial cases of IBD and in identical twins with IBD,15,16 highlights that shared environmental and genetic factors appear to shape disease phenotypic presentation.

Other potential risk factors include vitamin deficiency, psychosocial stressors, early cessation of breastfeeding, caesarean birth, exposure to infection in early life and antibiotic use.

Prevalence of inflammatory bowel disease

Australia and New Zealand reportedly have the highest IBD incidence in the world: in 2005 around 61,000 Australians were living with IBD, comprising 28,000 people with CD and 33,000 with UC.5 An estimated 1,622 new cases are being diagnosed every year – by 2020, the number of people with CD is projected to increase by 20% to around 33,500, while the number with UC is projected to increase by 25% to over 41,000.5

In 2005, around 61,000 Australians were living with IBD – 28,000 with Crohn’s disease and 33,000 with ulcerative colitis.5

Other high incidence areas include Northern Europe and North America. The occurrence of IBD is beginning to stabilise in high-incidence areas, however numbers are rising in low-incidence areas such as southern Europe, Asia and much of the developing world.

Sign and symptoms of inflammatory bowel disease

IBD symptoms depend on the location and amount of intestinal tract involved in the disease. Symptoms range from mild to severe during relapses, and may decrease or disappear entirely during remissions.

Typical symptoms include diarrhoea (with or without bleeding), abdominal pain, rectal bleeding, weight loss, nausea and vomiting. IBD patients also frequently suffer from chronic conditions affecting other organs.

There is no single diagnostic test that can reliably diagnose all cases of IBD and numerous tests may be required. In suspected IBD, tests distinguishing IBD from infectious gastroenteritis, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) and coeliac disease are considered. Investigations also help in defining disease activity and severity.

Characteristics of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis

More females than males

All ages, usual onset 15-35 years

Smoking

Higher risk for smokers

Symptoms

Diarrhoea, fever, sores around the anus, abdominal pains and cramps, pain and swelling in the joints, anaemia, fatigue, loss of appetite, weight loss

Similar for males and females

All ages, usual onset 15-45 years

Smoking

Lower risk for smokers

Symptoms

Bloody diarrhoea, mild fever, inflamed rectum, abdominal pains and cramps, fatigue, loss of appetite, weight loss, pain and swelling in joints

Adapted from Access Economics. The economic costs of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. 2007.5

Management of inflammatory bowel disease

A multidisciplinary approach is taken to the management of IBD, including input and care from gastroenterologists, colorectal surgeons, general practitioners, IBD nurses, radiologists, dietitians and psychologists. It is increasingly recognised that maintaining remission and anticipating problems, and thereby preventing complications, is an effective management strategy compared with managing acute disease episodes.

Management of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis

Drug treatment (aminosalicylates, corticosteroids, immune modifiers, antibiotics, biologic therapies)

Diet and nutrition

Surgery (repair fistulas, remove obstruction, resection and anastomosis)

Cure

Incurable

Maintenance therapy is used to reduce the chance of relapse

Complications

Obstruction or blockage of intestine due to welling or formation of scar tissue, sores or ulcers (fistulas), malnutrition

Drug treatment (aminosalicylates, corticosteroids, immune modifiers, antibiotics)

Surgery (rectum/colon removal)

Cure

Through colectomy only

Maintenance therapy is used to reduce the chance of relapse

Complications

Bleeding from ulcerations, perforation (rupture) of the bowel, abdominal distension

Adapted from Access Economics. The economic costs of Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. 2007.5

For people with IBD on corticosteroid therapy or with low or reduced bone mineral density, adequate calcium and vitamin D intake are important. In general, the aim should be to consume 3 to 4 serves of milk and dairy products each day and achieve sufficient sunlight exposure for optimising vitamin D levels. However, if dairy intake and sunlight exposure are inadequate, people with IBD many need to take calcium and vitamin D supplements.

The Gastroenterological Society of Australia (GESA) has prepared comprehensive guidelines for general practitioners and physicians on inflammatory bowel disease (IBD).

The Cancer Council Australia position statement on the risk and benefits sun exposure provides recommendations for sun exposure to maintain adequate vitamin D.

Irritable bowel syndrome

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is a chronic and relapsing functional gastrointestinal disorder (FGID) – FGIDs are considered ‘disorders of gut–brain interaction’.1,2

In IBS recurrent abdominal pain is associated with defecation or a change in bowel habits.3 Disordered bowel habits are typically present (ie constipation, diarrhoea or a combination of both), together with symptoms of abdominal bloating/distention. Symptom onset should occur at least 6 months before diagnosis and symptoms should be present during the past 3 months.3

Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) affects 5–12% of the population in western countries.3,4

IBS is the most common of the FGIDs, affecting approximately 5–12% of the population in western countries.3,4 It appears more complex than some other FGIDs, and may result from a combination of factors relating to motility, visceral hypersensitivity, mucosal immune dysregulation, alterations of bacterial flora, and central nervous system–enteric nervous system dysregulation.2 IBS presently has no known underlying pathology. Importantly, a number of common comorbidities are often also present and require exclusion.

Symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome

IBS is classified primarily in terms of symptoms2, which include abdominal bloating and excessive wind, abdominal distension and discomfort and altered bowel habits including bowel urgency, diarrhoea and constipation and a lack of satisfaction of stool emptying (ie “not all gone”). Arrival at a firm symptom-based diagnosis allows for reduced patient anxiety and also better management. However, exclusion of organic disease is a requirement.

The symptoms of IBS occur in the absence of any underlying pathology and present as a collection of symptoms that cluster as a syndrome.1,2

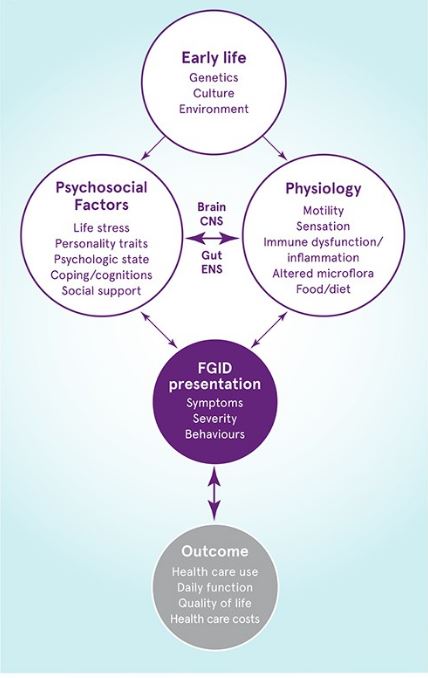

Without a mechanism to explain its clinical features, understanding of IBS is informed by a biopsychosocial model that takes into account the interactions between physiology, psychology and environment.1,2,5

A biopsychosocial model of functional gastrointestinal disorders

Adapted from Drossman 2016.2

Early life factors can influence psychosocial functioning, as well as their mutual interaction (via the brain-gut axis).

Together these factors inflluence the clinical presentation and clinical outcome of functional gastrointestinal disorders.

CNS, central nervous system; ENS, enteric nervous system.

Management of irritable bowel syndrome

Effective management of IBS commonly requires a multimodal approach including dietary, psychological and pharmacological interventions.2,6 The integrated effects of altered physiology and psychosocial status will determine the illness experience and, ultimately, the clinical outcome. In turn, outcomes affect the severity of the disorder. Consequently, psychosocial factors are essential to understanding IBS and for the development of an effective treatment plan.5

While IBS symptoms are not life threatening, they can be embarrassing, interfere with activities of daily living and impair quality of life, as well as affect health care use with significant economic impacts.7

There are four IBS subgroups recognised:2

- IBS with predominant constipation (IBS-C)

- IBS with predominant diarrhoea (IBS-D)

- IBS with mixed bowel habits (IBS-M) a syndrome of alternating diarrhoea and constipation

- unclassified IBS (IBS-U)

Determining whether a patient has a diarrhoea-predominant or a constipation-predominant IBS will inform further management.

Diagnostic criteria for irritable bowel syndrome

Recurrent abdominal pain, on at least 1 day per week (on average) in the past 3 months, and associated with 2 or more of the following criteria:3

• Related to defecation

• Associated with a change in stool frequency

• Associated with a change in stool form (appearance)

Symptom onset should have occurred at least 6 months before diagnosis.

Irritable bowel syndrome and milk intake

Some IBS patients may have reduced lactose absorptive capacity and may find that their IBS symptoms improve when their intake of dairy products is limited. In most patients, lactose intolerance is not the complete answer and other food triggers should also be considered. As limiting milk and dairy intake can have long-term health consequences, including effects on bone health, any ongoing reduction of milk and dairy intake should be assessed and reviewed by a dietitian.

Tolerance tips – for IBS patients symptomatic following lactose intake8

- Most people who are symptomatic following lactose intake can tolerate ~12 g of lactose (~1 cup of milk) as a single dose, particularly if taken with food, with no or minor symptoms

- A small number of people only tolerate smaller lactose doses (~3–5 g of lactose (¼ –½ cup of milk).

Patients with these levels of tolerance do not require a dairy-free diet, although consultation with a dietitian is advised to ensure adequate milk-micronutrient intake.

- For those who can tolerate only small lactose loads, lactase enzymes can be consumed when milk intake is increased (eg Lacto-Free®, available at pharmacies)

- Gradual lactose re-introduction may be useful to determine an individual’s lactose tolerance threshold

Irritable bowel syndrome and other dietary management

Monash University low-FODMAP diet

The Monash University low-FODMAP diet is an effective dietary treatment for managing IBS symptoms. In international studies, up to 86% of patients with IBS have achieved relief of overall gastrointestinal symptoms from the diet.9,10 The low FODMAP diet has become a first-line dietary therapy for IBS and is recommended in the Therapeutic Guidelines for Gastroenterology.

Up to 86% of patients with IBS achieved improvement in overall gastrointestinal symptoms from the low-FODMAP diet.9,10

A low FODMAP diet involves restricting foods that are rich in these short chain carbohydrates, under the guidance of a dietitian.

There are two phases of the low-FODMAP diet:

- Phase one: suspected FODMAP triggers are restricted from the diet for approximately 2–6 weeks to obtain symptom relief

- Phase two: the diet is broadened according to individual’s specific needs, informing diet choices for the longer term. In this phase, individual tolerance to FODMAP foods is determined in order to expand the diet. Patients with IBS differ in both the type and amount of FODMAP foods that they can tolerate before symptoms develop. This step is important as low-FODMAP dietary trials suggest a potential negative effect of dietary FODMAP exclusion if it is maintained for too long, primarily due to alterations in the microbiome with a reduction in potentially beneficial bifidobacteria.

What are FODMAPs?

FODMAPs (Fermentable Oligosaccharides, Disaccharides, Mono-saccharides and Polyols) are a group of foods containing short chain carbohydrates that include fructose (major sources include apples, pears, watermelon and honey); fructans (wheat, onion and garlic); galacto-oligosaccharides (GOS; legumes and nuts); lactose (milk and milk products); and the polyols (sorbitol in stone fruits and mannitol in mushrooms and snow peas).

These carbohydrates are poorly absorbed in the human small intestine due to inefficient transporters or insufficient specific enzymatic activity and so move through the intestinal tract, where they then interact with the intestinal microbiome. Healthy people without a digestive disorder may experience only some mild flatulence and natural laxation effects from FODMAP ingestion. However for IBS patients, in whom gut motility and microbiome may be altered, FODMAP ingestion results in the production of IBS-related symptoms.

FODMAP-containing foods contribute to the symptoms of IBS in the following ways:

- FODMAPs become a food source for colonic bacteria which ferment the FODMAPs and produce gases which result in abdominal distention and other subsequent symptoms

- FODMAPs are osmotically active and attract water to the colon –increased gas and water cause bowel distension alterations in motility which contribute to IBS-related symptoms of bloating, abdominal pain and altered bowel patterns

The Monash University low FODMAP Diet app for Android and iPhone is the first evidence-based smartphone application for practitioners and patients following the low-FODMAP diet and should be used in conjunction with dietetic advice.

The app provides detailed resources on the avoidance of foods high in symptom-causing fermentable carbohydrates, including suitable alternatives to ensure the diet is nutritionally adequate, to aid compliance and optimal symptom management.

Breath hydrogen testing

Breath hydrogen testing has been used previously as a diagnostic tool for fructose and lactose malabsorption (and as a surrogate measure of lactose and fructose intolerance responses) to drive low FODMAP dietary investigations and restrictions. However, the fructose breath test has since been found to be variable and change over time and is thus not useful in the individualisation of the low FODMAP diet. In addition, a hydrogen breath test will assess lactose absorptive capacity, but will not indicate whether an individual will be symptomatic following intake of lactose containing milk.11,12

Probiotics

There is insufficient good evidence to recommend a specific probiotic product. However, if a probiotic helps an individual it should achieve this within a few weeks. Probiotic supplementation may be ceased if no improvement occurs after this time. However, once a probiotic is stopped, the provided probiotic bacterial strain(s) will gradually cease to colonise the gut or reduce in numbers (so, the exogenous probiotic effects only last as long as the supplementation continues).

Psychosocial approaches

Gut-directed hypnotherapy and cognitive behavioural therapy have been shown to benefit patients with IBS.6 A psychologist specialising in gastrointestinal disorders with training in hypnotherapy can provide guidance to patients.

Looking for more information?

The Gastroenterological Society of Australia (GESA) is the peak professional body representing the specialty of gastrointestinal and liver disease in Australia.

Monash University low FODMAP diet for irritable bowel syndrome for information and resources for healthcare professionals and patients.

Coeliac disease

Coeliac disease is an immune-mediated chronic inflammatory disease caused by the ingestion of gluten-containing grains (eg wheat, rye and barley).1 It predominantly affects the gastrointestinal (GI) tract but can have widespread symptoms.1 Once considered a rare disease, improved clinical awareness and testing have contributed to its current recognition as a common lifelong disorder that can occur at any age, with a prevalence of 0.5–1.0% in Caucasian populations.1,2

Coeliac disease is recognised as a common lifelong disorder, occurring in 0.5–1.0% of the Caucasian population.1,2

Clinical symptoms associated with GI inflammation commonly include malabsorption, abdominal pain, constipation and diarrhoea. Other clinical features include coeliac disease antibodies (primarily tissue transglutaminase 2 IgA antibodies and endomysium IgA antibodies) and variable degrees of small intestinal mucosal damage, identifiable by biopsy.1

Risk factors for coeliac disease

Coeliac disease has a strong genetic basis – there is a high degree of disease concordance (~75%) in monozygotic (identical) twins compared with dizygotic twins,1,3,4 and its prevalence is 10–15% higher among people who have a first-degree relative with the condition.5 Coeliac disease is strongly associated with the human leukocyte antigen (HLA) genetic variants HLA DQ2.5 and HLA DQ8 and, despite regional variation, the correlation is generally ≥95%.1,4 Other less common genetic polymorphisms (eg HLA DQ2.2) account for the remaining small minority.1

HLA-based determination to identify genetic susceptibility to coeliac disease has become routine,1 however these genetic variants are found in 25–30% of most Caucasian populations despite the majority of individuals not expressing the disease phenotypically. The main role of HLA determination is thus to safely exclude coeliac disease, especially in patients already consuming a gluten-free diets.1

Signs and symptoms of coeliac disease

A considerable proportion of patients with coeliac disease have either no symptoms or subclinical symptoms (such as tiredness or irritability). Recognising the symptom pattern of coeliac disease will inform the need for further testing.1

Indications for coeliac disease testing include faltering growth, chronic or intermittent diarrhoea, constipation, abdominal pain, bloating or flatulence, prolonged fatigue, unexplained iron-deficiency anaemia or nutritional deficiency (as secondary to malabsorption), sudden/unexpected weight loss, low-trauma fracture or premature osteoporosis, abnormal liver function tests (especially elevated transaminases), and other separate manifestations of coeliac disease such as peripheral neuropathy, infertility or recurrent miscarriage, arthritis and epilepsy.1,6,7

Testing for coeliac disease

Testing for coeliac disease, except HLA genotyping, should be done while patients are on a sufficient gluten-containing diet providing about 3–6 g gluten/day (eg 2–4 pieces of wheat-based bread/day). If not, a sufficient gluten-containing diet needs to be eaten for 4–6 weeks before any testing can be performed.

Testing for coeliac disease, except HLA genotyping, should be done while patients are on a sufficient gluten-containing diet.

If the patient is reluctant or unable to consume a sufficient gluten-containing diet, then a coeliac disease gene test (ie HLA-DQ2/8 testing) can be performed to safely exclude coeliac disease. Remember, a positive HLA-DQ2/8 gene test is not diagnostic on its own: if it is positive, a 4–6 week challenge with a diet containing sufficient gluten will be required.1,8

After 4–6 weeks of exposure to a sufficient gluten containing diet, coeliac disease serology can then be requested. This includes tissue transglutaminase 2-IgA (tTG2-IgA) with deamidated gliadin peptide-IgG (PGD-IgG) OR tissue transglutaminase 2-IgA (tTG-IgA) with total IgA (to exclude the 2–3% of people with coeliac disease who are IgA deficient.1,4

Coeliac-specific serological tests now rival the accuracy of biopsy tests in many circumstances.1 However, biopsies remain an essential part of coeliac disease diagnosis in the vast majority of patients, even though duodenal biopsies might be avoided in a small minority of patients when specific serological, HLA and clinical criteria are met.1,4

Interpreting test results

If tTG2-IgA OR DGP-IgG is positive, then refer to a gastroenterologist to confirm coeliac disease with a small intestinal biopsy. If serology is negative but your patient is symptomatic and positive for HLA-DQ2 and/or HLA-DQ8, then consider referral to a gastroenterologist for further testing.9

Coeliac Australia has a range of resources to support general practitioners and other health professionals, including a Diagnosing coeliac disease fact sheet.

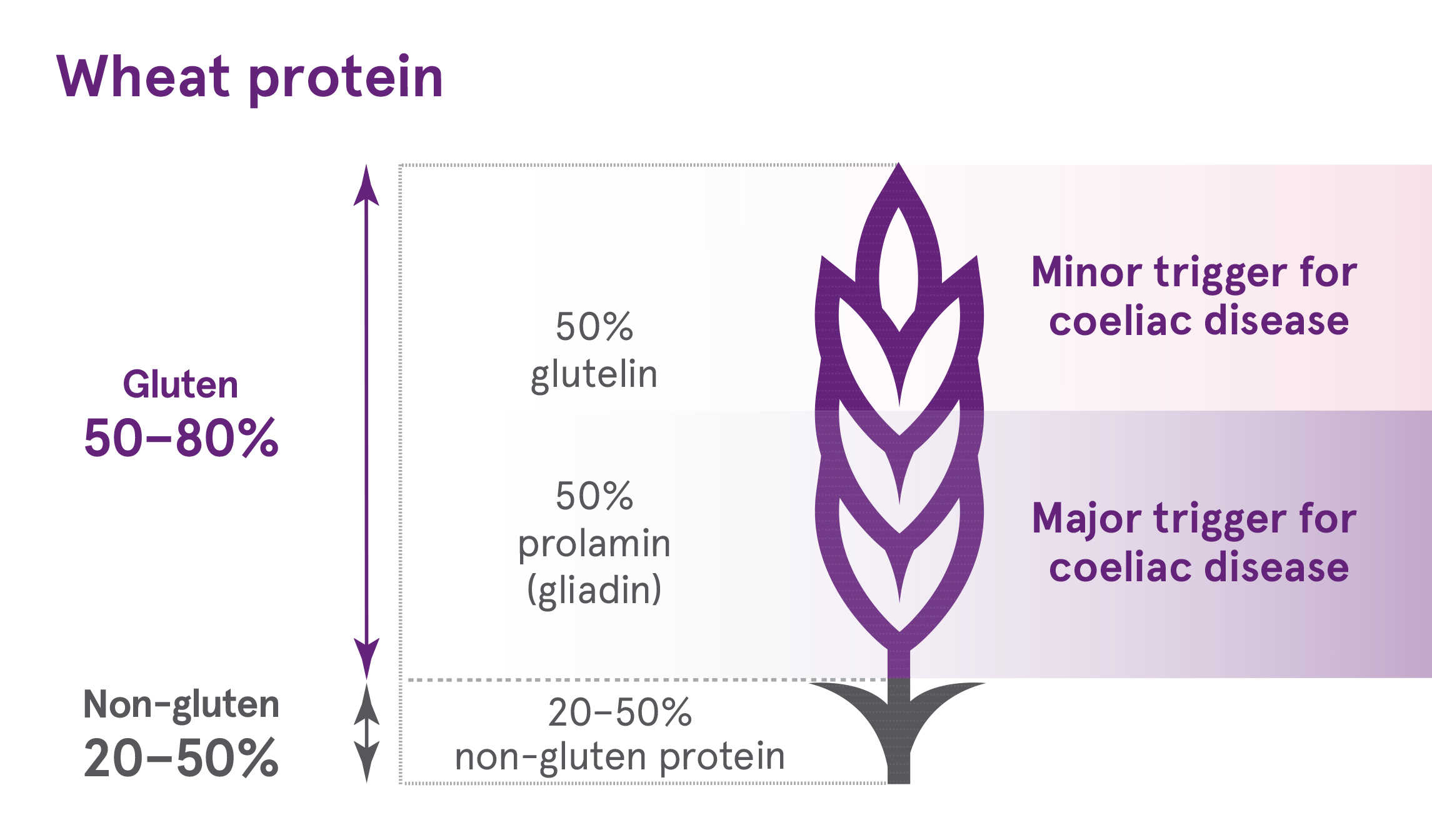

What is gluten?

The term ‘gluten’ is used to collectively describe the parts of grain storage protein (called prolamins) from wheat, rye, barley and oats.

The prolamins from each grain are different:

• Wheat – gliadin

• Barley – hordein

• Rye – secalin

• Oats – avenin

In people with coeliac disease, ingestion of these prolamins triggers an immune reaction.

In other grains, such as rye and barley, the total gliadin content is lower. For example, in rye, the total gluten content is lower than in wheat (<80% total protein) and the proportion of this that is a prolamin (called secalin) in is lower than in wheat (30–50% of rye gluten) – hence overall there is less prolamin in rye than wheat. However, a person with coeliac disease must avoid gluten entirely.

Management of coeliac disease

Long-term and strict compliance with the gluten-free diet is the only known management and is essential.10 Failure to adhere to a strict gluten-free diet can increase the risk of osteoporosis, poor growth, infertility, miscarriage, nutrient deficiencies including iron deficiency, gastrointestinal tumours (by 2-fold) and mortality (by 2-fold). Motivating benefits to patients for maintaining compliance include improved wellbeing, vitality and mental function.8,10

Coeliac disease and milk digestion

The lactase enzyme, which breaks down the milk sugar lactose, is produced in the epithelial cells lining the small intestine. Patients diagnosed with coeliac disease may develop a temporary or secondary lactose intolerance, likely due to damage to the lining of the small intestine, which then disrupts lactase production.11 However, most people with coeliac disease often tolerate lactose in their diet after around 3 months’ compliance with a coeliac (gluten-free) diet.

Patient information is available from the Gastroenterological Society of Australia (information about lactose intolerance/lactase deficiency) and Coeliac Australia (information about lactose intolerance).